Overview of the study

Using data from the 2022 Mental Health and Access to Care Survey, this article provides updated prevalence estimates for some of the most common mental disorders, including mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders. These results are compared to those from the previous 2012 and 2002 Canadian Community Health Survey – Mental Health cycles. The 2022 survey was collected from March to July 2022. This article also describes some key aspects of mental health care services in Canada. The analysis is focused on who Canadians turn to for mental health care, the role of virtual care in mental health care, and the types of mental care where the unmet needs for care are the largest.

- The percentage of Canadians aged 15 years and older who met the diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode, bipolar disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder has increased in the past 10 years, whereas the prevalence of alcohol use disorders has decreased, and the prevalence of other substance use disorders (including cannabis) has remained stable.

- Youth (ages 15-24), especially women, were most likely to have met diagnostic criteria for a mood or anxiety disorder based on their symptoms in the 12 months before the survey.

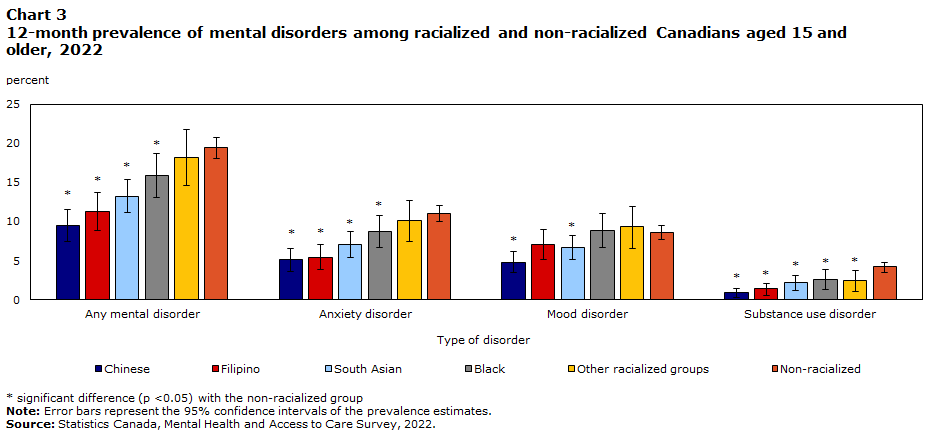

- The prevalence of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders was generally lower among South Asian, Chinese, Filipino, and Black people in Canada when compared to non-racialized, non-IndigenousNote people, although there were some variations in the magnitude of the differences depending on the type of disorder.

- About half of the people who met diagnostic criteria for a mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder talked to a health professional about their mental health in the 12 months before the survey.

- Among those who met diagnostic criteria for a mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder in the 12 months before the survey, 1 in 3 reported unmet or partially met needs for mental health care services.

- Unmet needs for counselling or psychotherapy were higher than unmet needs for medication or information about mental health.

End of text box

Introduction

Mental health challenges are a common experience. Most people will experience periods of better or worse mental health throughout their lives. However, some people will experience symptoms that are more severe, persist for a longer period, and impact their ability to function in everyday life. These people may meet the diagnostic criteria for a specific mental illness or mental disorder. Mental disorders are characterized by disruptions in thinking, mood, or behaviour and are associated with distress and impaired functioning.Note There are many different types of mental disorders, including mood disorders, anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, eating disorders, and substance use disorders.

Several studies have reported declines in population mental health over the past decade.Note With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020,Note some of these trends in mental health were exacerbated even further. In Canada,Note as well as other countries,Note large increases in the symptoms of depression and anxiety were observed in 2020 and 2021. These increases in symptoms of depression and anxiety were found to be especially pronounced among womenNote and younger people.Note However, there is limited information about the extent to which these increases in symptoms have resulted in a larger number of people who meet the diagnostic criteria for specific mental disorders.Note There were also increased strains on health care workersNote and challenges with access to health care servicesNote that may have contributed as well.

This study provides an update on the prevalence of specific mental disorders and mental health care in Canada using data from the Mental Health and Access to Care Survey (MHACS) that was collected in 2022.Note The study addresses two key research questions: 1) how many Canadians meet diagnostic criteria for specific mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders? and 2) Are those with a mental disorder getting the mental health care they need? The results will cover who Canadians turn to for mental health care, the role of virtual careNote in mental health care, and the types of mental health care where the unmet needs for care are the largest.

MHACS did not cover all forms of mental illness, but instead focused on identifying people who met the diagnostic criteriaNote for some of the most common mental disorders. Overall this study found that more than 5 million people in Canada met the diagnostic criteria for the following disorders: a major depressive episode, bipolar disorders, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia (social anxiety disorder), alcohol use disorder, cannabis use disorder, and other substance use disorders. To assess changes in the prevalence of these disorders over time, the estimates from MHACS were compared to the prevalence estimates from previous surveys completed in 2002Note and 2012.Note

More Canadians met criteria for a mood or anxiety disorder in 2022 than in 2012

The prevalence of selected mood and anxiety disorders was found to have increased substantially over the past 10 years (Table 1). The percentage of Canadians aged 15 years and older who met diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder in the 12 months before the survey doubled from 2.6% to 5.2% between 2012 and 2022. Similar increases were observed for the 12-month prevalence of major depressive episodes, from 4.7% in 2012 to 7.6% in 2022 and bipolar disorders, from 1.5% in 2012 to 2.1% in 2022. These increases in the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders were even larger among youth (see box Young women were the most likely to have met diagnostic criteria for a mood or anxiety disorder).

| Past 12 months | 2012 (ref.) | 2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percentage | 95% confidence intervals | percentage | 95% confidence intervals | |||

| upper bound | lower bound | upper bound | lower bound | |||

| Major depressive episode | 4.7 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 7.6Note * | 8.3 | 6.9 |

| Bipolar disorder | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 2.1Note * | 2.5 | 1.8 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 5.2Note * | 5.8 | 4.7 |

| Social phobiaTable 1 Note 1 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 7.1Note * | 7.7 | 6.4 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 2.2Note * | 2.6 | 1.8 |

| Cannabis use disorder | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.2 |

| Other drug use disorder | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Lifetime | ||||||

| Major depressive episode | 11.3 | 11.9 | 10.7 | 14.0Note * | 14.9 | 13.2 |

| Bipolar disorder | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 3.4Note * | 3.9 | 3.0 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 8.7 | 9.3 | 8.2 | 13.3Note * | 14.2 | 12.5 |

| Social phobiaTable 1 Note 1 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 7.7 | 14.6Note * | 15.5 | 13.7 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 18.1 | 18.9 | 17.3 | 16.7Note * | 17.7 | 15.7 |

| Cannabis use disorder | 6.8 | 7.4 | 6.3 | 6.8 | 7.6 | 6.2 |

| Other drug use disorder | 4.0 | 4.4 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 3.1 |

Start of text box

Young women were the most likely to have met diagnostic criteria for a mood or anxiety disorder

Some of the largest changes in the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders over the past 10 years were observed among womenNote Note aged 15-24 years old. The 12-month prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder among young women tripled from 3.8% in 2012 to 11.9% in 2022. Similarly, the prevalence of a major depressive episode in the past 12 months increased among young women, doubling from 9.0% in 2012 to 18.4% in 2022. The 12-month prevalence of a manic, hypomanic, or depressive episode among young women with a history of bipolar disorders also increased from 2.3% in 2012 to 8.1% in 2022.

Prevalence estimates in 2012 are not available for social phobia, though comparisons with 2002 suggests an increase. In 2002, 6.1% of women aged 15 to 24 met the criteria for social phobia. In 2022, the 12-month prevalence was 4 times higher, with 24.7% of women aged 15 to 24 years old meeting diagnostic criteria for social phobia. Although some of these changes may be related to increased stress during the COVID-19 pandemic,Note declines in mental health among youth were observed well before 2020.Note Across all the mood and anxiety disorders that were assessed in 2022, the 12-month prevalence rates were consistently highest among younger women (Chart 1).

Data table for Chart 1

| Age | Women+ | Men+ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percentage | Error interval (+/-) | percentage | Error interval (+/-) | ||||

| plus | minus | plus | minus | ||||

| Major depressive episode | 15 to 24 years | 18.4Note * | 3.1 | 3.1 | 8.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 25 to 44 years | 11.9Note * | 2.3 | 2.2 | 7.4 | 1.9 | 1.9 | |

| 45 to 64 years | 7.6 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 5.4 | 1.6 | 1.7 | |

| 65 years and over | 2.4 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.7 | |

| Bipolar disorders | 15 to 24 years | 8.1Note * | 2.2 | 2.3 | 3.7 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| 25 to 44 years | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| 45 to 64 years | 1.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.8 | |

| 65 years and over | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 15 to 24 years | 11.9Note * | 2.3 | 2.4 | 5.0 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| 25 to 44 years | 8.9Note * | 2.0 | 2.0 | 4.8 | 1.5 | 1.5 | |

| 45 to 64 years | 5.2Note * | 1.5 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 1.4 | 1.4 | |

| 65 years and over | 2.7 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 | |

| Social phobia | 15 to 24 years | 24.7Note * | 3.4 | 3.4 | 8.9 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| 25 to 44 years | 10.9Note * | 2.2 | 2.2 | 6.5 | 1.7 | 1.7 | |

| 45 to 64 years | 6.2Note * | 1.6 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | |

| 65 years and over | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.7 | |

End of text box

Substance use disorders did not follow the same trends as anxiety and mood disorders

Changes in substance use and availability can affect the prevalence of substance use disorders.Note In contrast to mood and anxiety disorders, the prevalence of substance use disorders did not increase from 2012 to 2022 (Table 1). The percentage of Canadians aged 15 years and older who met diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorders in the past 12 months decreased from 3.2% to 2.2% from 2012 to 2022. This decrease was primarily driven by a change among young men aged 15 to 24 years old. The percentage of young menNote aged 15 to 24 who met the diagnostic criteria for an alcohol use disorder in the 12 months prior to the survey decreased from 10.7% in 2012 to 4.8% in 2022. This is consistent with other data showing declines in heavy drinking among young men during this period.Note

Despite increases in cannabis use observed over the past decade,Note the 12-month prevalence of cannabis use disorders remained stable at 1.4% in 2022 (1.3% in 2012), as did the prevalence of other substance use disorders at 0.5% in 2022 (0.7% in 2012). Like in 2012,Note the 2022 data show that substance use disorders were more prevalent among men compared to women, and occurred most often among youth and young adults (Chart 2).

Data table for Chart 2

| Age | Men+ | Women+ | All genders | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percentage | Error interval (+/-) | percentage | Error interval (+/-) | percentage | Error interval (+/-) | ||||

| plus | minus | plus | minus | plus | minus | ||||

| 15 to 24 years | 10.1 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 6.7Note * | 2.4 | 2.3 | 8.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| 25 to 44 years | 6.2 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 4.2 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 5.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| 45 to 64 years | 2.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| 65 years and over | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Total – 15 years and over | 4.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 3.0Note * | 0.8 | 0.7 | 3.8 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

Start of text box

Prevalence of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders among racialized populations

The prevalence of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders was generally lower among South Asian, Chinese, Filipino, and Black people in Canada when compared to non-racialized, non-IndigenousNote people, although there were some variations in the magnitude of the differences depending on the type of disorder (Chart 3). This could be related to socio-cultural differences in willingness to report symptoms of mental illness or the stigma associated with mental illness.Note Other Statistics Canada surveys have found a similar pattern of results using measures of positive mental health (i.e., very good or excellent self-rated mental health).Note

Data table for Chart 3

| Type of disorder | Percentage | Error interval (+/-) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| plus | minus | |||

| South Asian | Any mental disorder | 13.2Note * | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Anxiety disorder | 7.1Note * | 1.7 | 1.6 | |

| Mood disorder | 6.7Note * | 1.6 | 1.5 | |

| Substance use disorder | 2.2Note * | 1.0 | 0.9 | |

| Chinese | Any mental disorder | 9.5Note * | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Anxiety disorder | 5.1Note * | 1.5 | 1.4 | |

| Mood disorder | 4.8Note * | 1.3 | 1.4 | |

| Substance use disorder | 0.9Note * | 0.6 | 0.5 | |

| Black | Any mental disorder | 15.9Note * | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| Anxiety disorder | 8.7Note * | 2.0 | 2.1 | |

| Mood disorder | 8.9 | 2.2 | 2.1 | |

| Substance use disorder | 2.6Note * | 1.3 | 1.3 | |

| Filipino | Any mental disorder | 11.3Note * | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| Anxiety disorder | 5.4Note * | 1.6 | 1.7 | |

| Mood disorder | 7.0 | 1.9 | 2.0 | |

| Substance use disorder | 1.4Note * | 0.8 | 0.7 | |

| Other racialized groups | Any mental disorder | 18.2 | 3.6 | 3.6 |

| Anxiety disorder | 10.1 | 2.6 | 2.6 | |

| Mood disorder | 9.3 | 2.7 | 2.6 | |

| Substance use disorder | 2.4Note * | 1.4 | 1.3 | |

| Non-racialized (ref.) | Any mental disorder | 19.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Anxiety disorder | 11.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Mood disorder | 8.6 | 0.9 | 0.9 | |

| Substance use disorder | 4.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 | |

End of text box

Half of the people who met diagnostic criteria for a mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder have not talked to a health professional about their mental health in the past year

There are many different types of health care providers that provide mental health care or who can support those with needs for mental health care. In Canada, this includes family physicians or general practitioners, psychiatrists, nurses, psychologists, psychotherapists, social workers, and counsellors, among others.Note Accessing mental health care services often involves talking to one of these professionals.

Among the 18.3% of Canadians aged 15 years and older who met diagnostic criteria for a mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder in the 12 months before the survey, about half (48.8%) reported that they had talked to a health professional about their mental health in the past year. They were most likely to report having talked to a family doctor or general practitioner (32.4%). Fewer people reported talking to a mental health care specialist such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, or psychotherapist (Table 2).

| Talked to any health professional | Talked to a family physician or general practitioner | Talked to a psychiatrist | Talked to a psychologist | Talked to a social worker, counsellor, or psychotherapist | Talked to a nurse | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percentage | 95% confidence intervals | percentage | 95% confidence intervals | percentage | 95% confidence intervals | percentage | 95% confidence intervals | percentage | 95% confidence intervals | percentage | 95% confidence intervals | |||||||

| upper bound | lower bound | upper bound | lower bound | upper bound | lower bound | upper bound | lower bound | upper bound | lower bound | upper bound | lower bound | |||||||

| People with a mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder | 48.8 | 51.9 | 45.6 | 32.4 | 35.3 | 29.4 | 12.7 | 14.9 | 10.5 | 11.4 | 13.3 | 9.5 | 21.0 | 23.6 | 18.5 | 5.2 | 6.7 | 3.7 |

| People without a mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder | 10.3 | 11.3 | 9.4 | 5.8 | 6.5 | 5.1 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| All Canadians | 16.8 | 17.7 | 15.9 | 10.1 | 10.8 | 9.3 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 5.5 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 1.2 |

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual modes of healthcare delivery were greatly expanded. Note Among Canadians who talked to a health professional about their mental health, the majority did so in-person (57.0%) or over the telephone (51.4%). Video calls were also used, but this varied based on the type of provider (Table 3). More people who talked to a psychiatrist (25.3), psychologist (45.1%), or social worker, counsellor, or psychotherapist (37.6%) reported using video, compared to those who talked to a family doctor or general practitioner (5.1%) or a nurse (9.7%). It is possible that some forms of treatment, like psychotherapy, are more amenable to the use of video for appointments.Note

| Type of health care provider | In-person | Telephone | Video | Text Messaging | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percentage | 95% confidence intervals | percentage | 95% confidence intervals | percentage | 95% Confidence intervals | percentage | 95% Confidence intervals | |||||

| upper bound | lower bound | upper bound | lower bound | upper bound | lower bound | upper bound | lower bound | |||||

| Any health professional | 57.0 | 60.2 | 53.8 | 51.4 | 54.5 | 48.4 | 27.7 | 30.5 | 24.9 | 3.3 | 4.5 | 2.2 |

| Family doctor or general practitioner | 58.8 | 63.0 | 54.7 | 53.4 | 57.5 | 49.3 | 5.1 | 6.9 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 0.6 |

| Psychiatrist | 49.2 | 56.2 | 42.2 | 48.8 | 56.2 | 41.4 | 25.3 | 31.3 | 19.3 | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act |

| Psychologist | 40.7 | 47.1 | 34.3 | 26.7 | 32.3 | 21.1 | 45.1 | 51.6 | 38.5 | 3.0 | 5.1 | 1.0 |

| Social worker, psychotherapist, or counsellor | 41.8 | 47.0 | 36.5 | 38.4 | 43.4 | 33.3 | 37.6 | 32.8 | 42.4 | 3.4 | 5.2 | 1.7 |

| Nurse | 54.6 | 65.1 | 44.1 | 45.2 | 55.6 | 34.8 | 9.7 | 16.6 | 2.8 | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act |

Many people who met diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder reported needing more counselling or psychotherapy than they received

People who met diagnostic criteria for mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders were more likely to report having received counselling (43.8%), than medication (36.5%) or information (32.0%) for their mental health. However, they also reported greater unmet needs for counselling services, relative to medication or information needs (Table 4).

Six in 10 (58.8%) people who met diagnostic criteria for a mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder in the 12 months preceding the survey reported needing counselling or psychotherapy services, but only 43.8% reported receiving some counselling or psychotherapy services. Among those who did receive counselling or psychotherapy, 64.3% felt that their needs for mental health counselling services were met. This suggests that even when people with mental disorders do access mental health care, it is often unsuccessful in meeting all their perceived needs. Almost all the people who received medication for their mental health (92.0%) reported that their needs for medication were met. The availability and accessibility of medication and counselling services are likely influenced by different factors.Note

| Type of care | Partially met needs | Fully unmet needs | Either partially or fully unmet needs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percentage | 95% confidence intervals | percentage | 95% confidence intervals | percentage | 95% confidence intervals | ||||

| upper bound | lower bound | upper bound | lower bound | upper bound | lower bound | ||||

| Information | 6.1 | 7.7 | 4.4 | 11.7 | 13.8 | 9.5 | 17.7 | 20.3 | 15.1 |

| Medication | 2.9 | 4.0 | 1.9 | 4.1 | 5.4 | 2.8 | 7.0 | 8.7 | 5.4 |

| Counselling | 15.6 | 18.0 | 13.2 | 14.9 | 17.1 | 12.7 | 30.5 | 33.4 | 27.7 |

| All types | 25.8 | 28.7 | 22.9 | 10.9 | 12.8 | 8.9 | 36.6 | 39.7 | 33.6 |

Conclusion

Findings from the Mental Health and Access to Care Survey suggest in 2022, there were more than 5 million people in Canada who were experiencing significant symptoms of mental illness. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on population health and access to health services are among the many factors that may have contributed to the high prevalence of mental illness observed. However, declines in population mental health were evident in Canada before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.Note

There were large increases in the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders, compared to data collected in 2012. This finding is consistent with findings from other countries.Note Given the high prevalence rates observed among youth, more research is needed to understand the unique mental health challenges facing young people today. Adolescence and young adulthood are known to be developmental periods in which the risk for mood and anxiety disorders is heightened.Note However, there is a growing body of research that suggests that the prevalence of major depression and anxiety disorders among youth today is higher than it was for previous generations.Note The effects of the pandemic on mental health were also greater for young people compared to older age cohorts.Note As we move beyond the COVID-19 pandemic,Note it will be important to continue monitoring whether the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders continues to remain high or even continues to increase. In addition, future studies on the prevalence and trends in mood and anxiety disorders should examine differences within and across vulnerable populations, such as the 2SLGBTQ+ population.Note

The results of this study indicate that not all needs for counselling and psychotherapy services are met. There are often long wait times for community mental health counselling,Note as well as additional barriers to the affordability and accessibility of these services.Note Family physicians remain the most common source of support for people seeking professional help for mental health.Note Family physicians also spend much of their time treating anxiety and depression — these are among the most common reasons for an appointment with a family physician.Note Administrative health data suggest that primary care providers have seen an increase in visits for mental health concerns since 2020,Note especially among children and adolescents.Note Increasing the supply of health care providers who focus on mental health and have specific training in this area is one of many possible solutions to improve access to mental health care in Canada.Note However, disparities in health insurance coverage for medicationsNote and counselling servicesNote will also need to be addressed.

Ellen Stephenson is an analyst for the Centre for Population Health Data at Statistics Canada.

Start of text box

Data sources, methods, and definitions

Data sources

The primary data source was the Mental Health and Access to Care Survey (MHACS), a survey of Canadians ages 15 years and older living in the 10 provinces. The survey was completed by 9,861 respondents from March 17 to July 31, 2022. The sample was selected from the population that completed the long-form questionnaire of the 2021 Census. To evaluated changes in the prevalence of specific mental disorders over time, data from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey – Mental HealthNote and 2002 Canadian Community Health Survey: Mental Health and WellbeingNote were also used.

MHACS was administered using an interviewer-assisted electronic questionnaire (iEQ), which differs from to 2012 and 2002 versions of the survey which were administered in person. Excluded from the survey’s coverage are: persons living on reserves and other Aboriginal settlements, full-time members of the Canadian Forces, and persons living in collective dwellings, such as institutional residences.

Definitions

Mental disorders

MHACS used a modified version of the World Health Organization – Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WHO-CIDI)Note to classify people with select mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Although this is not a clinical diagnosis, this is a standardized instrument that is used to assess mental disorders in population surveys according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders version IV (DSM-IV) criteria.Note A fifth edition of the DSM was published in 2013 and the revised classification of disorders might affect some prevalence estimates; however, a revised version WHO-CIDI was not available at the time of the survey collection. To facilitate comparison, the same definitions were used for social phobia in 2002Note and for all the other disorders in 2012.Note

Prevalence estimates for each disorder included both whether diagnostic criteria were met at any point in the lifetime (lifetime prevalence) or within the 12 months before completing the survey (12-month prevalence). This study used 12-month prevalence estimates when evaluating use of mental health care services among people with mental disorders.

Diagnostic criteria for the following disorders were assessed:

- Mood disorders

- Major depressive episode (depression): is identified as a period of 2 weeks or more with persistent depressed mood or loss of interest in normal activities, as well as other symptoms including: decreased energy, changes in sleep and appetite, impaired concentration, feelings of hopelessness, or suicidal thoughts.

- Bipolar disorder : includes respondents who meet the criteria for bipolar I disorder or hypomanic episode, which includes bipolar II disorder. It is characterized by at least 7 days (or fewer if hospitalized) of exaggerated feelings of elevated or irritable mood plus a certain number and combination of other manic symptoms such as racing thoughts, talking more than usual, excessive spending, decreased need for sleep, increased pleasure seeking activity, or exaggerated self-confidence. Many people also experience at least one depressive episode.

- Anxiety disorders

- Generalized anxiety disorder is identified by a pattern of frequent, persistent worry and excessive anxiety about several events or activities lasting at least 6 months along with other symptoms.

- Social phobia (social anxiety disorder) is characterized by a persistent, irrational fear of situations in which the person may be closely watched and judged by others, as in public speaking, eating, or using public facilities.

- Substance use disorders include both substance abuse and substance dependence. They can be further subdivided based on the substance involved.

- Substance abuse is characterized by a pattern of recurrent use where at least one of the following occurs: failure to fulfill major roles at work, school or home, use in physically hazardous situations, recurrent alcohol or drug related problems, and continued use despite social or interpersonal problems caused or intensified by alcohol or drugs.

- Substance dependence is when at least three of the following occur in the same 12 month period: increased tolerance, withdrawal, increased consumption, unsuccessful efforts to quit, a lot of time lost recovering or using, reduced activity, and continued use despite persistent physical or psychological problems caused or intensified by alcohol or drugs.

- Alcohol use disorder includes those who met the criteria for abuse or dependence of alcohol.

- Cannabis use disorder includes those who met the criteria for abuse or dependence of cannabis.

- Other drug use disorder (excluding cannabis): includes those who met the criteria for abuse or dependence of substances such as club drugs, cocaine, heroin, solvents, prescription drugs used for nonmedical reasons, and any other illicit drugs.

Mental health care by provider type and format of care delivery

All respondents were asked “During the past 12 months, have you seen or talked on the telephone or over the Internet to any of the following people about problems with your emotions, mental health or use of alcohol or drugs?”

- Psychiatrist

- Family doctor or general practitioner

- Psychologist

- Nurse

- Social worker, counsellor, or psychotherapist

- Family member

- Friend

- Co-worker, supervisor, or boss

- Other – Specify

The first five response options were used to define those who had talked to a health professional about their mental health in the past 12 months.

For each health professional selected above, respondents were asked how they talked with that person. They could select any of the following options that applied to them: a) in person, b) over the telephone (voice only), c) using video on a phone, tablet or computer or d) text message or written chat.

Perceived needs for mental health care

The assessment of unmet needs for mental health care was based on questions adapted from the Perceived Need for Care Questionnaire (PNCQ).Note

On MHACS, all respondents were asked if they had received four main types of help:

- Information about the problems, treatments or available services

- Medication,

- Counselling, therapy or help for problems with personal relationships

- “other” types of help.

They were then asked if they felt they needed each of the types of help they had not received and if they felt they needed more of the types of help they had received.

For each type of help, four groups were created:

- No need – people who were not receiving help and felt that they had no need for it;

- Need fully met – people who were receiving help and felt that it was adequate;

- Need partially met – people who were receiving help, but not as much as they felt they needed;

- Need not met – people who were not receiving help, but felt that they needed it.

A composite variable was created with the same four categories to define perceived needs for all types of help.

Strengths and limitations of using surveys to study mental health and access to care

The data used in this study rely on the accuracy of the survey respondents’ self-reports. Current mental health status may bias the recall of mental health symptoms and health care that was received in the past.Note It is also possible that those who received treatment and experienced improvements in their mental health will not be captured among those who currently meet diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder. Administrative data are not subject to these self-report biases and can provide information about on use of mental health services and diagnoses of mental disorders in clinical settings. However, an important strength of MHACS is that these data can be used to estimate the burden of mental illness in the entire population, not just those who have accessed health care services or who have received a formal diagnosis. This study showed that many people with clinically significant symptoms have not even talked to a health care provider about their mental health.

End of text box