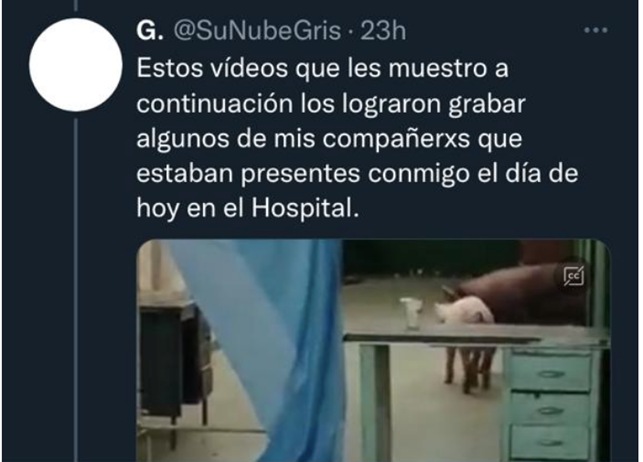

In preparation for a course on clinical community psychology at my home university in Caracas, Venezuela, I stumbled upon a tweet from an anonymous student complaining about a family of pigs that had occupied the psychiatric hospitalization ward where he was supposed to develop his clinical training. The Tweet seemed preposterous, until you consider the gravity of the deterioration of the public health system and that the Tweet was accompanied by pictures and a video of a group of pigs roaming carelessly through the hospital.

After sharing with the class the most recent example of utter abandon of the psychiatric system as a way to stress the need to rethink the ethical grounds of our profession and the strategies to attempt to resolve this huge crisis, a student asked to talk to me afterwards in private. She was visibly worried about this episode, expressing that another classmate was the one who had posted the Tweet, after which he had been threatened for exposing the situation.

This episode is almost incomprehensible unless you begin to grasp the dimensions of the political, social and economic crisis that Venezuela has endured for almost a decade. Examined up close, it is a revealing piece that illustrates the abuse of the levels of dehumanization that have led to gross human rights abuse and also shines a light on the causes of this horror.

I myself was a bit perplexed at first, striving to understand why this student was feeling so threatened. I asked to speak to him directly and he welcomed the invitation. He explained to me that his supervisors were worried that the military personnel that manage the hospital were going to react angrily over feeling exposed about the dysfunction of the institution. That they might prohibit the university, which has a tense relationship with the government, from continuing to develop its academic practice on these grounds. This worry turned into blame, his supervisors admonishing the student for having shared the insides of the hospital, accusing him of betraying the professional confidentiality that clinical practice requires.

His explanation left me distraught. I have followed the continuous deterioration of the mental health system for years, collaborating with the development of alternative networks and treatment options to try to buffer consequences. A few years back, I hesitated before publicly denouncing the deterioration of another psychiatric center, the El Peñón psychiatric hospital, after hearing the pleas of various colleagues who argued that public outcry would only worsen the government’s persecution of the medical professionals that were struggling to continue to offer assistance in dire circumstances.

But this episode was doubly worrying. On the one hand, it evidenced the ongoing dismantling of the public health system, but on the other and even worse, the fear of speaking out, the silent acceptance of militaristic demands for complicity in the midst of abuse, disguised as “confidentiality”.

I called the supervisors and asked “Whose rights are we protecting? Those that are suffering and ask for professional assistance? Or those of the hospital directors who do not want to be challenged regarding their failure to provide the minimum conditions for providing assistance?”

The Collapse

The mental health system can only be described as an utter collapse, in the midst of what has been described as a complex humanitarian crisis by international aid organizations. Access to decent medical attention is in crisis in general but, as tends to be the case, attention to the psychological sufferings is even worse off.

The national and international press have been calling attention to the gravity of the situation for almost ten years now. As far back as 2014, for example, an article reported that workers of the Psychiatric Hospital of Caracas at Lídice, which had one of the main public psychiatric hospitalization wards in Caracas, held a protest about patients’ conditions that included lack of food; while another report denounced that in the El Peñón psychiatric hospital, windows had been closed with cement to avoid patients from escaping, that corruption ran rampant, and that even parking spaces were being rented out to private car owners from the neighborhood.

The general landscape of the psychiatric system was reported as grossly lacking in relation to the demands of the population, with 11 psychiatric centers and 78 outpatient centers having an average of a five-month waiting list to provide attention. Professionals were described as avoiding reporters for fear of being persecuted.

By 2016, international press reports had picked up on the situation. The New York Times titled a piece “Inside Venezuela’s Crumbling Mental Hospitals”, describing the Pampero hospital where patients complained of being hungry. There was no soap, no shampoo, no toilet paper, and there was hardly any medicine as doctors were barely present. By 2020, a local newspaper reported that 10 patients had died from hunger at that same hospital.

In 2019, a Washington Post title speaks for itself: “Locked up Naked on a Soiled Mattress: Venezuela’s Mental Health Nightmare”. In it, the downfall that was apparent in 2014 had taken a huge toll, as the previously mentioned El Peñón Hospital reported having had 14 patients die because of lack of resources. The pleas to avoid clashing with the government did not avert its demise. In particular gruesome instances, some patients have died painful deaths over infections that went untreated because of lack of antibiotics.

In 2022, we developed a nation-wide survey on the impact of Covid-19 on psychological suffering in Venezuela and the availability of attention. A team of newspaper reporters called the 264 public centers listed by the health ministry during three months, only 11 of these answered the calls, but out of this meager 4% of listed services, only half had an operative psychological service.

Interviews with colleagues that continue to work in the public health sector report having received unofficial orders to avoid all hospitalizations. This means there are no public places to treat a person in crisis. For example, the Hospital Universitario de Caracas, one of the most progressive services in the past, recently had only one hospitalized patient. She remained in the center since she had no family or home to be sent back to. One of the many worries of the service directors was that, without patients, the postgraduate training program is practically pointless.

This is all without listing the use of psychiatry to persecute political enemies that Venezuela’s government has engaged in, which leads to another dimension altogether, even though it complements our comprehension of the nature of the beast we are facing.

But Why the Pigs?

But how does all this explain pigs roaming freely in a public hospital during a worldwide pandemic? Well, it happens that the directors of the hospital, considering the empty spaces provided by its lack of services, decided to allow a family of homeless “milicianos” to move in. A miliciano is, literally, a militiaman, and in Venezuela it refers to a revolutionary category that implies someone who is ideologically committed to the revolution and is willing to take up arms if necessary, even though they are not formally in the armed forces. In practice they are sympathizers who are used for small tasks like bulking up pro-government rallies, or other political manifestations in exchange for unofficial gifts and perks from government. These milicianos, living in the hospital premises, happened to be raising pigs for their personal consumption. Seeing that the hospital was pretty much abandoned, they decided to free them from their cages and allow them to roam around. This detour to the bizarre details of this episode is relevant to grasp the militaristic dynamics that frame and explain the causes of the country’s collapse.

What Next?

Enduring the same challenges that the struggle that psychiatric users have had in the rest of the world, and with many transformations still waiting to happen, this collapse, however, points to another level of human rights abuse. Venezuela not only has a huge pending agenda regarding the incorporation of the many new developments in relation to patient-led policies for mental health services, it has also regressed to the horrors of nineteenth-century psychiatric wards, including gross dehumanization.

The collapse of the traditional system could, from an optimistic standpoint, be an opportunity to develop and strengthen alternative, community- and patient-led approaches to mental health. But such a dire situation demands previous actions that include rendering visible the plight of many that, at this point, have very little voice in the midst of an economic, social, and political crisis that pushes mental patients’ struggles to invisibility. We first need to raise awareness and counter the fears of political persecution over denouncing this situation, which have engulfed the mental health community.